One of the most misunderstood topics in gardening is something that should be relatively straightforward - where our gardens are located in commonly used classifications of climate zones, and how that affects what we can grow.

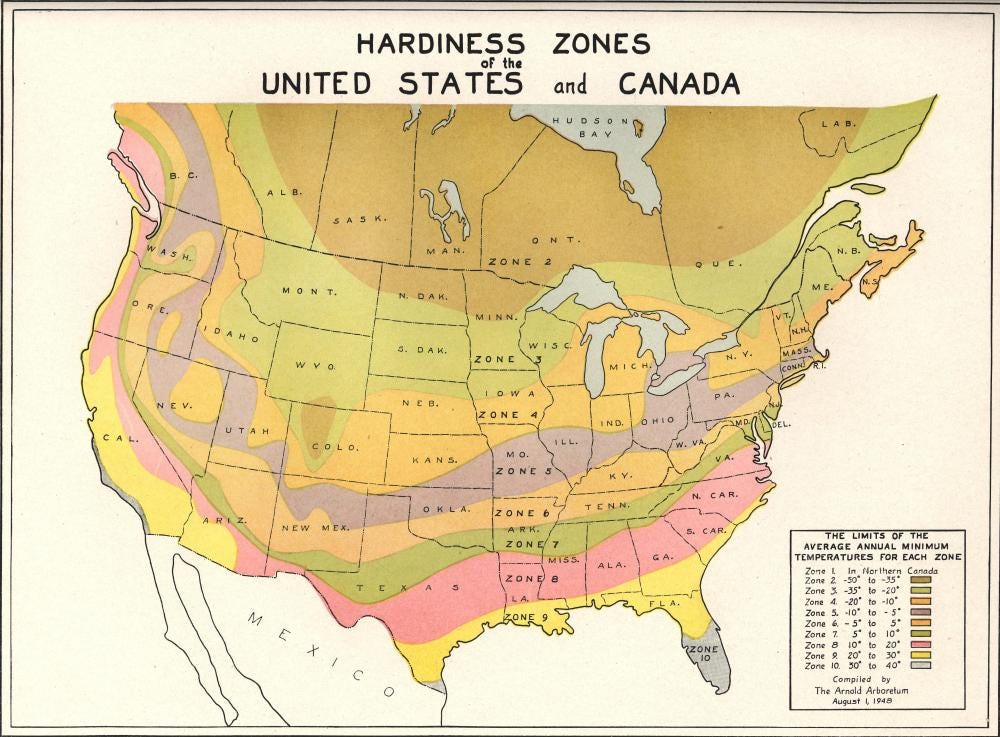

The zone map that's typically referred to is promulgated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, with the most recent update released in 2012:

Along with this release, the U.S.D.A. added an interactive feature so you can type in your zip code to locate your climate zone. Two new zones were added (12 and 13). Most people wound up with homes shifted a half-zone downward i.e. from zone 6a to 6b. According to the U.S.D.A. “…some of the changes in the zones are a result of new, more sophisticated methods for mapping zones between weather stations. These include algorithms that considered for the first time such factors as changes in elevation, nearness to large bodies of water, and position on the terrain, such as valley bottoms and ridge tops. Also, the new map used temperature data from many more stations than did the 1990 map.”

The latest map is the culmination of efforts that began with the first primitive attempts at rendering climates into neat sectors as a guide to growers and gardeners, dating back to the early 19th century, as described in this history.

A major misunderstanding among gardeners involves the basic premise of the map, the average coldest winter temperature. Some people, after a few unseasonable winters with extremes warmer or colder than usual, think that the U.S.D.A. got it wrong and they’re in a different zone. Then reality strikes. For instance: the past two years at my central Kentucky location (zone 6b) featured winter lows of 9F and 4F, which would put me smack in the middle of zone 7 (average winter low of 0 to 10 degrees F). Then came the deep freeze of December ‘22, when a low of -9F hit - a zone 6a-style temperature. Back to zone 6b (or 6b-7a, if you insist) we go. David Francko, in his book “Palms Won’t Grow Here And Other Myths” (an excellent source for zone-defying gardeners) noted that during a single decade (1990-2000), only one winter fell within the range of zone 6a where his garden was located. Every other winter the winter minimum fell into a zone warmer or colder - annual extremes during the period were -24F and 7F. I well remember two winters in central Kentucky from my time in Lexington in the late ‘80s to early ‘90s, when a couple winters had drops to near -20F. If I’d accepted that as defining my climate zone and choices, I’d have missed out on a lot of great plants.

Within a given zone, there are a ton of factors that contribute to microclimates not reflected on the zone map. These involve such things as elevation (valleys often experience colder temps than hills), nearness to buildings and bodies of water, exposure to winds, soil moisture levels and so on. Another element is summertime heat, which can improve winter survival by allowing certain plants to build up greater food stores. A “borderline” plant growing in the relatively cool summer climate of the Pacific Northwest coast might be severely damaged or killed by temperatures well above zero, while the same plant growing in a southern plains state could survive untouched at a much lower winter minimum.

That brings us to the American Horticultural Society heat-zone map, developed in the late ‘90s as a complement to the U.S.D.A. map. It stratifies the U.S. into zones based on the number of days each year when the temperature rises above 86F, which is supposed to be a magic number at which plants begin to stress out and suffer damage. Intuitively this sounds great, a logical system by which to select plants that can handle your summer conditions. In practice it’s not so hot, as myriad other factors (extent of heat waves, nighttime cooling, humidity, rainfall etc.) complicate things and in my opinion, make the AHS heat-zone map considerably less useful than the U.S.D.A. guidelines.

Need more maps to add to enlightenment and confusion? We’ve got ‘em.

One of the more colorful yet bewildering systems is the Köppen-Geiger classification of world climate. Work behind this one began in 1900 and continues to the present day. On moving back to central Kentucky I was bemused to find that according to the Köppen-Geiger gang, I’m living in a “humid subtropical” climate. While it may feel that way during the summer, it seems ridiculous at other times, as during our previously noted cold wave of late December 2022 when a polar front dropped the temperature to -9F. Not exactly weather for shorts, flip-flops and harvesting avocados from the tree in your front yard.

The National Arbor Day Foundation issued this climate zone map in 2015. I find it a trifle…optimistic when it comes to establishing how a warming climate affects your garden. It might be most useful to those in serious zone denial.

But what about the Sunset zone map? Sunset magazine came out with its debut set of 13 zones (later expanded to 24) covering western states, greatly subdividing areas (especially in California) to account for their vagaries in heat/cold, terrain and oceanic influences. It was supplemented in 1997 by the Sunset National Garden book which extended zone definitions to cover the rest of the country. Unfortunately, these “eastern” zones seem less well thought-out and the accompanying descriptions of what grows well there are relatively simplistic. I found that my (at the time) central Ohio garden was stuck in the same zone with south-central Michigan, and that in the view of Sunset editors I was pretty well limited to tough native perennials to survive my allegedly harsh winters. The encyclopedia accompanying the book was similarly discouraging about using plants with which I’d already succeeded or was planning to try. The Sunset people, like other authorities in mild climates, come off as sniffy about the idea of gardeners in less favored climes daring to work with plants that are not “suited” for their locale.

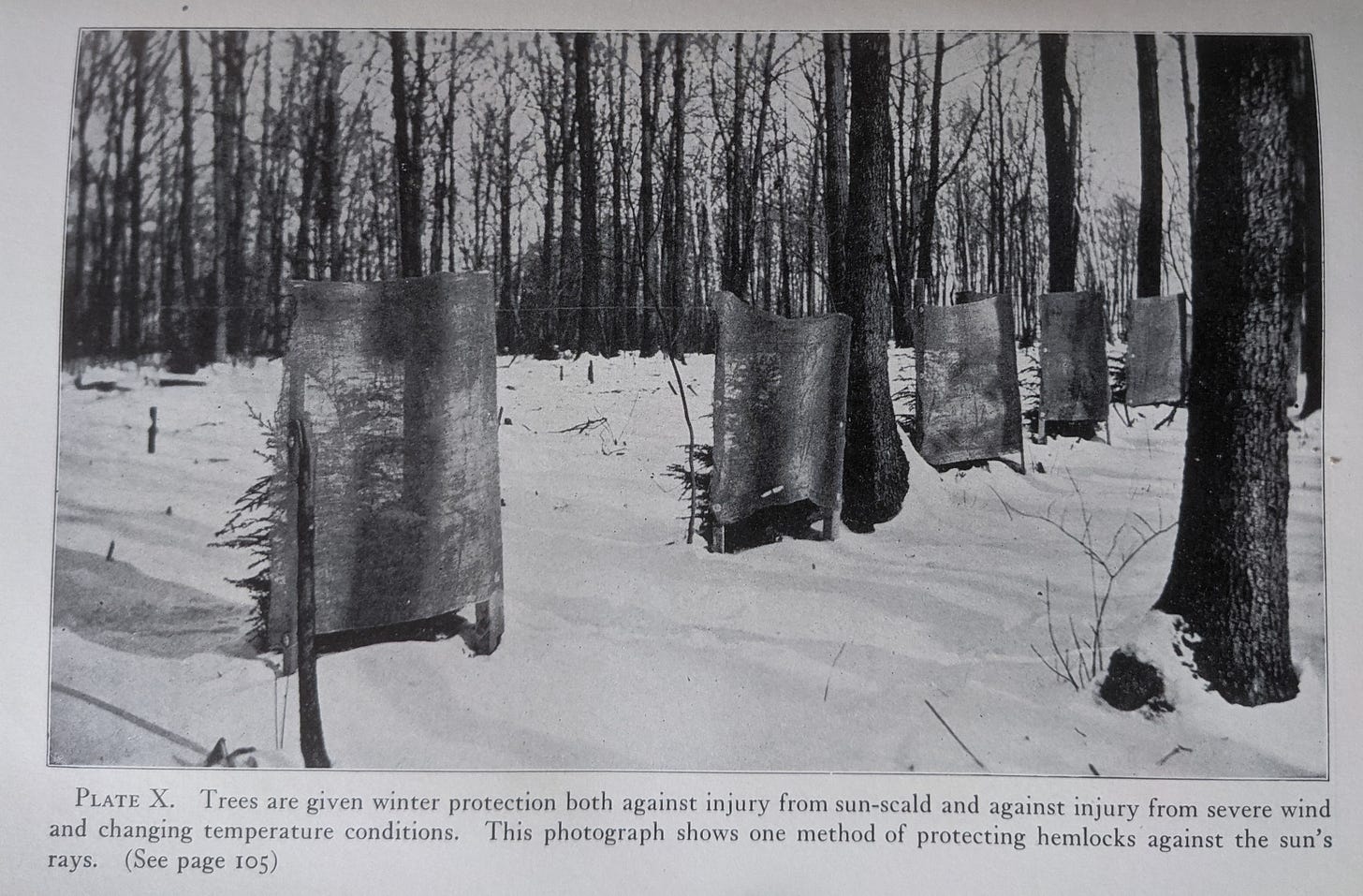

Similarly rebellious sorts enjoy surmounting the imperfections of climate rating systems, by working with their gardens’ microclimates and unique features and employing protection systems to defy what Nature has to offer. That gardening philosophy will be explored in a future post.